It is exactly 10 years since I first set foot on the blighted Greenwich Peninsula. Blinking innocently in the coruscating light of the new Blair dawn, I had accepted a curious invitation to give some badly needed creative direction to the already foundering millennium project. They wanted a 'creative director' and had called me in my quiet Chelsea office to make me that offer I could never refuse. 'You want to spend a billion on architecture and design and you're asking me to help? Promise to let me get on with it?' 'Yes,' they said, in what I now see as a bravura exercise in spin. They only wanted a rubber stamp.

I said I would rush off and ask brains such as Susan Sontag and Umberto Eco what they would do (just to check). And we would have Norman Foster design a miniature city of the future for the world's great architects, designers and artists to fill. And then I was told we could not have foreigners! It got worse, and I left after six months of high-pressure misery, deceit and bungling.

Peter Mandelson was moaning the other day that the millennium had left no permanent remains worthy of note, neglecting to add that it was entirely his fault that this was so. Well, that's all changed now. Something very substantial has been built on the site... but it is not what anybody expected back in 1997. In those days the Greenwich Peninsula was a toxic bog. Years of slovenly processing activity by British Gas had left the area irredeemably polluted by carcinogens. Trucks leaving the site had to pass through wheel-washers to cleanse their tyres of contamination. Breathing apparatus was available for contractors. As if there were not enough pollution in the air, the deadly cocktail was complemented by the amusing decision to build the Millennium Tent over an exhaust vent of the Blackwall Tunnel. Looking back, we should have seen all this as a portent of horrors to come.

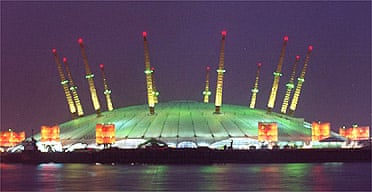

I say 'Tent' because the Millennium Dome is nothing of the sort, a dome being a self-supporting masonry or brick vault of rounded profile. But the modest word Tent was not congruous with the triumphalist pomp of New Labour, so the first of this government's many idealised economies with the truth was presented to the public. Still, the cable-stayed tent that Buro Happold engineered from an idea by architects Richard Rogers and Partners was an elegant, if dauntingly impractical, building design.

It is tempting to suggest that the Tent was something Rogers had long wanted to build rather than something known to be needed for the project in hand. Its conceptual history goes back to the Fifties when a German architect called Frei Otto was working with the great Richard Buckminster Fuller at Washington University in St Louis. These were hero figures to Rogers's generation. Each was interested in lightweight structures of ambitious, possibly even megalomaniac, character. In 1964 Otto created the Institut fur Leichte Flaechentragwerke in Stuttgart's Technical University and in 1967 used its expertise to build the West German Pavilion at the Montreal Expo. The following year Fuller proposed a two-mile diameter geodesic dome to be placed over New York to improve the weather.

The engineers Buro Happold caught the 'dome infection' too. In 1981 they proposed a covered 'City in the Arctic'. What was being built in 1997 as my wellies slopped in the Greenwich goo was the result of this history: the largest membrane structure in the world, a polymer tent supported by tensioned cables arranged radially around a dozen 100m masts made of open steelwork. I never knew whether the result looked more like the segment of a vast globe sinking melancholically into the bog or one rising in an optimistic symbol from it. Still, the speed with which the Tent passed into the iconography of London says a lot about the quality of its design.

But it was not an intelligent design, even if it was an impressive structure. It produced a space so vast it hobbled the imagination of those charged with filling it. Choose your own tabloid imagery: the Eiffel Tower, laid on its side, would sit comfortably in the Tent. There are the 18,000 customary double-decker buses. Or 12 football pitches. When asked, David Hockney said it would be best left empty, but New Labour abhorred a vacuum so it was filled with patronising rubbish. And when that was cleared away, it was left in pitiable desuetude. Little of the promised regeneration was stimulated by its presence, and a fine new Tube station at North Greenwich by Will Alsop promised only the grating absurdity of delivering 30,000 passengers an hour to visit diddly-squat.

Tony Blair said the Tent would be on the first page of his second manifesto, one of many claims later economised. Instead it became an embarrassment, more an annoying pustule than an imperious duomo. Despite its vast size, the remote location helped minimise the humiliation, but finding a new use was a government priority. Proposals of different levels of reality came and went. Prescott went into action. And the result was the announcement in 2005 that the Tent was to be acquired by the Los Angeles-based Anschutz Entertainment Group, whose business philosophy is to provide 'The Ultimate Fan Experience'. This they did at the Manchester Evening News Arena, until selling it last year, and still do at Toyota Park and the Nokia Theatre in New York's Times Square. In addition, about 18 per cent of US cinemas are owned by AEG. And, in case I forget, as proprietors of the Los Angeles Galaxy soccer team, AEG also owns David Beckham.

Tonight the Millennium Tent re-opens as the O2 Arena. What has happened inside the Tent is extraordinary, not least because it has been virtually covert. Since there is a roof already in place, construction of a vast 23,000 arena could not be achieved with conventional tower cranes. Instead, tools called stand-jacks were used to build from the ground up. The result is astonishing: if anything, the Tent filled with a building looks more frighteningly huge than it did empty. The arena was designed by HOK Sport, the American specialist architectural firm also responsible for the Emirates Stadium. And around the arena are the handmaidens of that 'Ultimate Fan Experience', over 25 catering concessions rented to Gaucho Grill, Pizza Express, Starbucks, Zizzi, Nando's, The Slug and Lettuce. There will be an internal beach, and visitors will not have to wait any longer than seven seconds to have their pint poured. The arena will host the 2012 Olympics gymnastics. In this fashion, whatever vengeful local gods were ired by millennial hubris may, possibly, be gratified.

My enthusiastic guide, who described herself as 'a Beckham co-worker', ex-plained that the architecture of this dazzlingly vulgarian food mall, this corridor of grease, is Art Deco. True, there may be stylistic reflections of Sunset Boulevard's NBC Radio City or the Hollywood Bowl, but it is not as simple as that. While the arena itself looks technoid with high-voltage this, low-voltage that and lots of exposed conduit, channels and projectors, the mood here on 'The Street' is different. You are invited to have an ambulatory experience among tectonic forms (I don't think they can be called 'architecture') that are vaguely ice-cream and Egyptianate in inspiration. Indeed, for those who tire of attractions such as Nando's, Andrea Bocelli, hockey and Bon Jovi there is space which will soon host a vaguely museological Tutankhamun event (I don't think it can be called 'exhibition').

With technology and kitsch, pizza and Beckham co-workers, AEG has achieved something remarkable. It is a strange experience to be in a building within a building, and not one which agoraphobes, aesthetes or sociopaths will enjoy, but at last something coherent has been achieved on the Greenwich Peninsula. Form and content are as one, and that's not something anyone thought of 10 years ago. And with massive new groundworks sanitising the bog, there is not even a whiff of toluene. It was not just the presence of an American corporation that created 'The Ultimate Fan Experience', but the absence of political interference. In 1997 that seemed very unlikely too.

What they said then

Run-up to the millennium

· It will be London's answer to the Eiffel Tower.

Millennium Dome Commission, November 1996.

· Not so much the millennium's Crystal Palace, more a post-modern hedgehog.

Independent, November 1996

· A white elephant at a disused gasworks in Greenwich.

Sun, May 1997

· A social and environmental disaster of which the state government of Amazonas would be proud.

George Monbiot, Guardian, June 1997

· With its little Sputniks stuck to the edges, its floating walkways and its spiky bits emerging from the ceiling like Dame Barbara Cartland on a Bad Hair Day, I felt a sense of nostalgia for the novels by John Wyndham.

Craig Brown, Daily Telegraph, June 1997

· We will say to ourselves with pride: this is our Dome, Britain's Dome. And believe me, it will be the envy of the world.

Tony Blair, February 1998

· Even God doesn't like the Millennium Dome...

Daily Mirror, June 1999 [when it was hit by lightning]

· Have you ever noticed that the Millennium Dome looks like a giant cervical cap?'

Kathy Lette, Daily Telegraph, June 1999

2000 and beyond

· A triumph of insignificance. Las Vegas does this sort of thing much better.

Gerard Mortier, artistic director of the Salzburg Festival

· Hindsight is a wonderful thing, and if I had my time again I would have listened to those who said governments shouldn't try to run tourist attractions.

Tony Blair, October 2000

· In 12 traumatic months [it] went from being Britain's great white hope to its great white elephant.'

Sunday Express, December 2000

· I wish I could rewind the clock, invent a time machine and kill those crazy two numbers.'

Pierre-Yves Gerbeau, chief executive of the Millennium Dome, on the erroneous forecast of 12 million visitors

Robert Collins