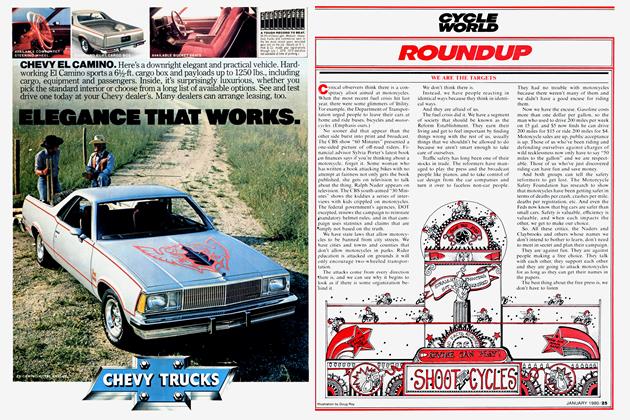

HONDA CB400T

The U.S. Version of the Sporting Hawk Is a 400 We Rode for Fun, not Duty

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The 1980 CB400T Hawk isn’t what we expected when we heard that Honda planned to introduce an American version of the popular, European-model CB400N. We had dreamed of the Euro-Hawk’s twin

front disc brakes, 750F-styling, rearset footpegs and low bars, six-speed transmission and three additional horsepower.

What we got was the swoopy styling, sixspeed transmission and the 1979 engine modified to meet stringent 1980 ERA emissions standards.

But what we also got was a 400-class machine that sporting-minded staffers actually enjoyed riding, a bike even those jaded by high-horsepower Superbikes would ride for fun instead of out of pure devotion to duty. If the maximum performance, mega-power freaks at this magazine were sentenced by some bizarre court to serve out the rest of their careers riding 400cc motorcycles, the Hawk is the bike they'd pick.

Interestingly, the 1980 Hawk isn’t the fastest and quickest 400 we’ve tested. Our test bike turned the standing-start quartermile in 14.29 sec. with a terminal speed of 89.19 mph. After a half-mile run, the Hawk reached a top speed of 98 actual

For comparison, the 1979 Yamaha RD400F turned the quarter in 14.19 sec. at 91.37 mph, and had an identical top speed of 98 mph after a half-mile run. And the quickest Hawk we’ve ever seen—a 1979 Type II—turned 14.08 sec and 90.90 mph.

But there is more to this than may meet the eye. First off. we have no way of knowing or predicting how the 1980 emissions standards will affect the performance of the RD400, nor do we know at this time whether or not there will even be a 1980 RD400. We do know' that every 1980 model we’ve seen—with the exception of the Honda CB750F—has deteriorated in performance compared to its 1979 counterpart.

Then there is the matter of comparing a five-speed 1979 Hawk to a six-speed 1980 Hawk. Further complicating things is the question of break-in and jetting. The test bikes we receive from manufacturers often have less than 100 miles on the odometers from a cursory, quick, none-too-easy break-in. The 1979 Type II Hawk which turned the stellar (for a 400) time of 14.08 is the basis of the Cycle World production racing project. It was jetted to 1978 Hawk specifications and was lovingly and carefully broken in by CW contributor Pat Eagan. The break-in distance was longer 250 miles—and the main object was to continually vary throttle settings for best break-in. not to hurry up and get a bike to a magazine tester.

The best E.T. we had ever gotten out of a test Hawk prior to this 1980 model was 14.40 at 87 mph for a drum-brake, lightweight Type 1 and 14.57 at 86.20 mph for a heavier Type II w ith disc brake and electric starter (top speed 99 mph).

The point of all this is that for all we know, the CB400T may well be the quick-> est and fastest 1980 400-class motorcycle you can buy. But for all our uncertainty on the question of absolute performance, we are very certain of this: There isn't a 400 we’d rather ride.

Consider the comparison to the RD400F. The RD bucks, refusing to hold a steady, constant speed around town in low rpm. small throttle-opening situations. The RD also seems to present the rider with a choice of two ways to leave a stop light: front wheel in the air, or engine lugging along off the powerband.

The Hawk, on the other hand, is perfectly happy putting around town with the throttle barely open and will leave the light with a good, smooth power delivery at just about any engine speed the rider chooses between 2000 and 10.000. As the revs rise, the power increases, as is expected, but there isn't any point along the power curve where all hell breaks loose. Because of that, the Hawk is an ideal learner’s bikeno abrupt surges in power means fewer surprises for the novice. Yet if the rider uses the six-speed gearbox to keep revs up. the Hawk will fly down the road at high speed with a lot less effort than other 400s we’ve ridden.

The Hawk loves to rev. and w here some other 400s seem to flatten out on top. the Honda still pulls in sixth gear and is less affected by things like hills and headwinds, things which have a power-sapping effect on bikes like the Yamaha XS400—which doesn’t seem to have much power to start with—and demand a quick downshift (or two) on the RD400, which makes power but along a much narrower spread of rpm than the Hawk.

And while the Hawk delivers more power across a wide rpm range than the other 400s. it's also smoother than any other Twin in its class.

The power comes from the well-known, three-valve Hawk cylinder head and oversquare powerplant. Bore is 70.5mm while stroke is 50.6mm, and that wide bore makes plenty of room for lots of valve area, with two intake valves and a single exhaust valve. The smoothness comes from two counter-rotating balancer shafts driven by a chain off the crankshaft to reduce the vibration inherent in a vertical Twin with crank throws spaced 360° apart.

New technology was added to the Haw k engine to meet 1980 emissions standards, which were unexpectedly stiff ened up after the Hawk design was completed in 1976. According to Honda spokesmen, the Hawk was built to comply with expected 1980 standards at the time of its introduction, but the standards tightened up and sent the engineers back to the drawing boards.

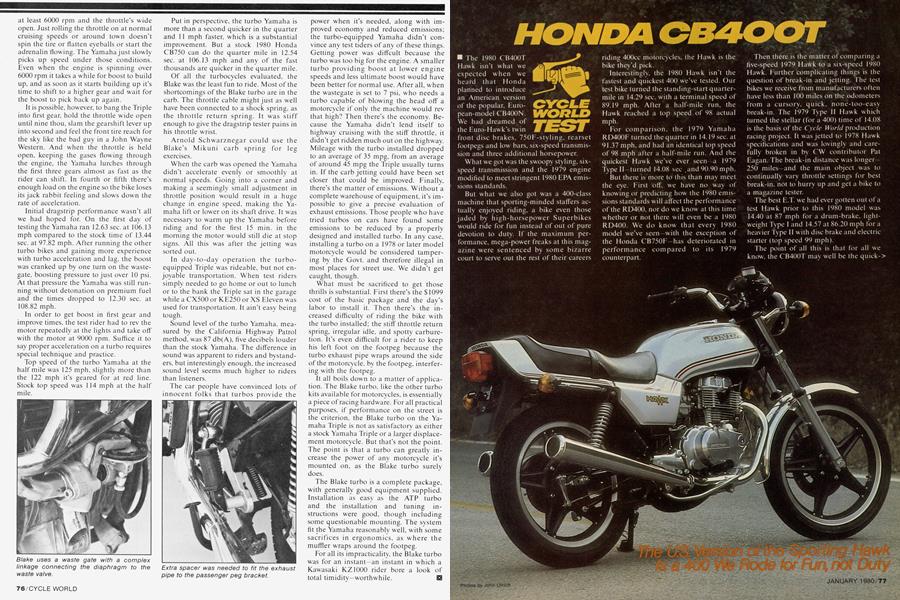

The engineers replaced the 1979 Hawk’s 32mm Keihin CV carburetors with 30mm Keihin CVs, and then followed the standard Honda approach to meeting EPA requirements—lean out the idle circuit at mid-range, install an accelerator pump to overcome lean-jetting hesitation ofl' idle, and leave the main jet big enough for fullthrottle performance. More precisely, the primary jet (which is uncovered just off idle by the butterfly throttle disc) in 1979 was a #75, and is reduced to a #70 in 1980. But the secondary, main jet is a # 110 in 1980. actually larger than 1979’s #105. The slow jet is smaller in 1980, a #38 compared to 1979’s #42.

The pistons are different in the 1980 Hawk, with smaller domes to match reshaped-combustion chambers designed to promote cleaner burning and thus meet EPA standards. The piston and chamber revisions were necessary because the new jetting caused detonation with the 1979 head and piston. Compression ratio remains the same at 9.3:1, but the changes to the pistons and combustion chambers are dramatic.

Despite the changes to reduce emissions, Honda claims that the 1980 Hawk has the same horsepower as the 1979 Hawk. The dragstrip figures tend to support that claim, and one side benefit of the changes is improved gas mileage. On the Cycle World test loop, a mixture of city streets and highways, the Hawk returned an astounding 57 mpg when ridden at close to the posted speed limits. Obviously, the faster and harder you ride, the less miles you can go per gallon. But the Hawk’s mileage loop figures are still plenty remarkable for a sporty bike when compared to other bikes ridden at the same speeds over the same route. (The RD400F returned 44 mpg, the Suzuki GS425 got 52 mpg, the XS400F delivered 58 mpg, the Kawasaki KZ400 made 62.5 mpg, and the 1977 Hawk Type II did 47 mpg).

Even though the carburetion is leaner and the fuel economy up, the Hawk is still easy to start on a cold morning, which is just the opposite of many machines. All the rider has to do is pull out the handlebar-mounted choke knob, hit the electric starter and either let the Hawk idle away or else ride right off down the street, pushing the choke in after a mile or two. No hesitation, no false starts, no dying engine, just start and go, nice and simple.

Unrelated changes to the 1980 Hawk include the obvious styling and seat shape, and the deletion of the entire kickstart mechanism. Honda spokesmen say that the styling links the Hawk to the 750F and CBX in Honda’s “High Performance Series,” while the kickstart is no longer necessary because the charging system is so strong that needing to kickstart a Hawk shouldn’t ever be necessary.

While the strong electrical system may make a kickstarter unnecessary, it is fair to say that the reasoning behind the new seat is probably less logically motivated. Sure, it looks great, but the seat might as well be stuffed with iron marbles, judging by its effectiveness in promoting rider and passenger comfort. The seating position is better and the bars more comfortable than found on semi-choppers, but everybody who rode the bike commented on the perverse seat, and one beginner asked innocently after his first ride “Is this seat very comfortable compared to most motorcycles?”

The suspension, too, was a lot less compliant than we’ve become accustomed to. If there are small, repetitive bumps on the roadway, then you’ll feel them, even with the shocks set at the lowest preload—even > when packing a passenger. Same goes for the forks. But when you turn the Hawk onto a twisty road, none of that matters. What matters is that the Hawk does what it’s told and does it quickly and predictably.

It handles. Suddenly your buddies on the 750s and 1000s who delighted in pulling away on the interstates are scratching for their honor as you and the Haw k stuff' it in deeper at tight turns and gas it up sooner coming out. In the twisties, the Hawk is great, the more curves the better. It’s easy for the intelligentsia of motorcycling to crack jokes about Honda’s “Diamond Frames,” which use the engine as a stressed member and which may be used as much for production-line convenience and cost effectiveness as for the Hondaproclaimed handling benefits. But the fact is, the Hawk frame (and the forks and the stamped sheet metal top triple clamp if the lower triple clamp bolts are kept tight) works plenty well, thank you. and it’s still faultless after you mount up a set of road racing slicks and head for the racetrack.

That’s right, faultless. The street bikes which can stand the addition of sticky slicks without complaining and without wobbling are few and far between, and there the Hawk shines.

Where it doesn't gleam is in the braking department. The Hawk doesn’t do badly, stopping in 33 ft. from 30 mph and in 135 ft. from 60 mph, compared to the RD400’s 37 ft. and 131 ft., the GS425’s 32 and 141 ft., the XS400’s 33 and 138 ft. What the figures don’t show is that the Hawk’s front brake is not progressive enough. It demands a lot of hand pressure, w hich means the rider can go from less-than-maximum stopping power to locked front wheel in a very short span of micro-seconds.

Now. There isn't any indisputable advantage to dual front disc brakes. They weigh more and add unsprung weight, which hampers the suspension. On a light bike, when done properly, the single front disc should be as good or better than the dual system.

But in the Hawk’s case, the single disc lacks the progressive control it should have, and Honda already has the dual discs fitted to the European Hawks, and in sum we wish they'd used that system on the American sporting Hawk.

It could be argued that the six-speed transmission looks better in theory than it works on the road. Hawk racer Eagan says the five-speed used in the earlier Hawks is just fine, and one staff member asks, if they have to have a six-speed, why is it geared so that the engine turns about the same rpm in top gear as it did with the five-speed? (The 1980 Hawk turns 5500 rpm at 60 mph in sixth; the earlier five-speed Hawks turned 5662 at 60 mph.) Why not an overdrive sixth?

The answer, of course, is that this is a sporting machine and sporting machines have six-speeds. After all, how does it look to have a “sporty” machine with a fivespeed when all the other 400s have sixspeeds? The fact is, the Hawk powerband is plenty wide for a five speed, but on the other hand, having a six-speed doesn’t really hurt anything in street use. It does require an extra shift before the lights at the drag strip, possibly losing time and if the owner should somehow' find some way to crank an extra five or 10 horsepower out of the engine, he won’t be hurting it if the powerband is narrowed up a bit.

Where there can be no argument at all is in the styling department. The Hawk looks great. A lot of people who saw the bike did double-takes and asked “How big is it?” It does look like the 750F and the CB900FZ sold in Europe. The people at Honda U.K. even told us that they get complaints from CB900FZ owners that the 400s look too much like the bigger bikes, and that they don’t like that one bit. Not bad from the 400 owner’s viewpoint—who wouldn’t want a 400 that fooled people into thinking for a moment that it was a 750 or 900?

With the Honda Hawk CB400T you get big-bike styling, good manners around town, transportation convenience, and sporting fun all at once.

We give it an A +.

HONDA CB400T

SPECIFICATIONS

$1798

PERFORMANCE