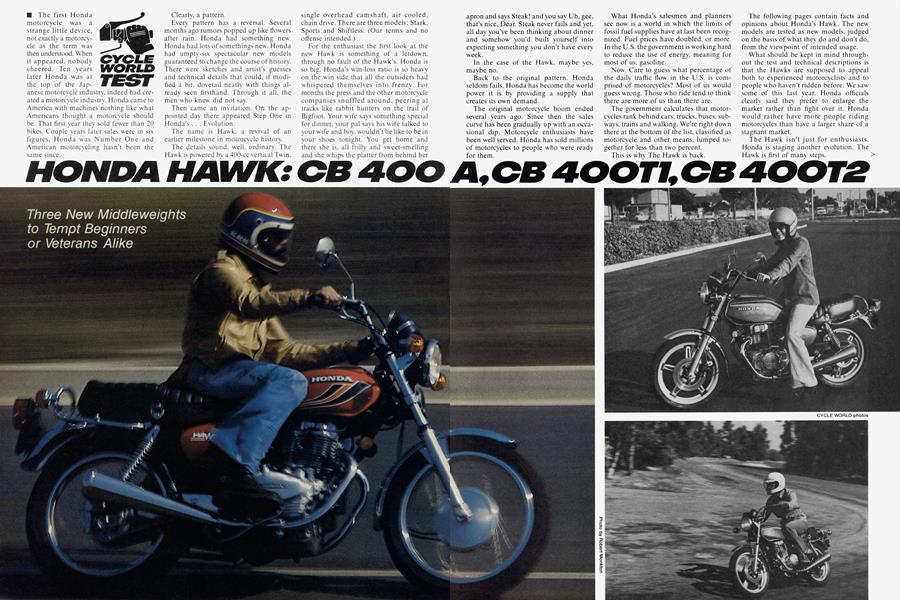

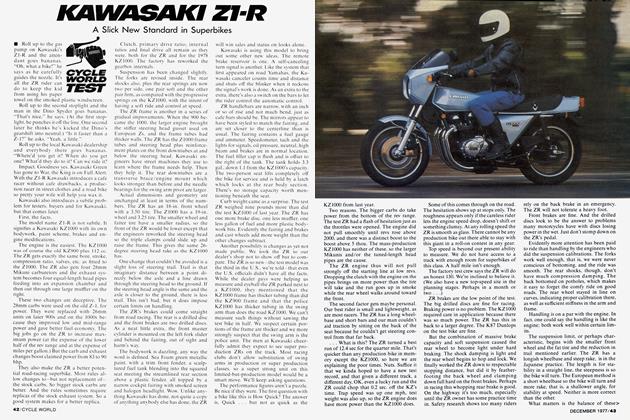

HONDA HAWK: CB 400 A, CB 400T1, CB 400T2

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Three New Middle weights to Tempt Beginners or Veterans Alike

The first Honda motorcycle was a strange little device, not exactly a motorcycle as the term was then understood. When it appeared, nobody cheered. Ten years later Honda was at the top of the Jap-

anese motorcycle industry, indeed had created a motorcycle industry. Honda came to America with machines nothing like what Americans thought a motorcycle should be. That first year they sold fewer than 20 bikes. Couple years later sales were in six figures, Honda was Number One and American motorcycling hasn't been the same since.

Clearly, a pattern.

Every pattern has a reversal. Several months ago rumors popped up like flowers after rain. Honda had something new. Honda had lots of somethings new. Honda had umpty-six spectacular new models guaranteed to change the course of history. There were sketches and artist’s guesses and technical details that could, if modified a bit. dovetail neatly with things already seen firsthand. Through it all, the men who knew did not say.

Then came an invitation. On the appointed day there appeared Step One in Honda’s . . . Evolution.

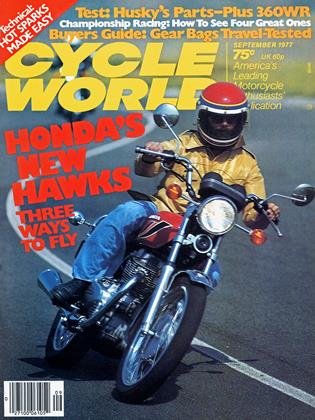

The name is Hawk, a revival of an earlier milestone in motorcycle history.

The details sound, well, ordinary. The Hawk is powered by a 400-cc vertical Twin,

single overhead camshaft, air cooled, chain drive. There are three models; Stark, Sports and Shiftless. (Our terms and no offense intended.)

For the enthusiast the first look at the new Hawk is something of a letdown, through no fault of the Hawk’s. Honda is so big, Honda’s win-loss ratio is so heavy on the win side that all the outsiders had whispered themselves into frenzy. For months the press and the other motorcycle companies snuffled around, peering at tracks like rabbit hunters on the trail of Bigfoot. Your wife says something special for dinner, your pal says his wife talked to your wife and boy, wouldn’t he like to be in your shoes tonight. You get home and there she is, all frilly and sweet-smelling and she whips the platter from behind her apron and says Steak! and you say Uh, gee, that’s nice, Dear. Steak never fails and yet, all day you’ve been thinking about dinner and somehow you’d built yourself into expecting something you don’t have every week.

In the case of the Hawk, maybe yes, maybe no.

Back to the original pattern. Honda seldom fails. Honda has become the world power it is by providing a supply that creates its own demand.

The original motorcycle boom ended several years ago. Since then the sales curve has been gradually up with an occasional dip. Motorcycle enthusiasts have been well served. Honda has sold millions of motorcycles to people who were ready for them.

What Honda’s salesmen and planners see now is a world in which the limits of fossil fuel supplies have at last been recognized. Fuel prices have doubled, or more. In the U.S. the government is working hard to reduce the use of energy, meaning for most of us, gasoline.

Now. Care to guess what percentage of the daily traffic flow in the U.S. is comprised of motorcycles? Most of us would guess wrong. Those who ride tend to think there are more of us than there are.

The government calculates that motorcycles rank behind cars, trucks, buses, subways, trains and walking. We’re right down there at the bottom of the list, classified as motorcycle and other means, lumped together for less than two percent.

This is why The Hawk is back.

The following pages contain facts and opinions about Honda’s Hawk. The new models are tested as new models, judged on the basis of what they do and don’t do, from the viewpoint of intended usage.

What should be kept in mind throughout the test and technical descriptions is that the Hawks are supposed to appeal both to experienced motorcyclists and to people who haven’t ridden before. We saw some of this last year. Honda officials clearly said they prefer to enlarge the market rather than fight over it. Honda would rather have more people riding motorcycles than have a larger share of a stagnant market.

The Hawk isn’t just for enthusiasts. Honda is staging another evolution. The Hawk is first of many steps.

Other companies have tried the variations-on-a-basic-theme approach to motorcycle marketing but with the introduction of its new Hawks, Honda appears to have perfected it. Instead of putting out models that are merely dressed up or dressed down versions of the same thing, Honda offers this: three bikes that are largely the same where it counts—handling, ride and basic layout—and different where it counts—styling, go and. of course, price.

Although these three machines aren’t quite as dramatically new and different as some of the advance build-up led us to believe, they are nevertheless pure Honda in conception and execution. If your aim is to revolutionize the market by making it substantially larger, the evolutionary changes in your product should be aimed at breaking down traditional resistance wherever possible. Honda has already revolutionized the motorcycle business with a brilliantly conceived image-building effort that has long since blown the old whipsand-chains karma that once hung over bikes and bikers. “You meet the nicest people on a Honda.” Suddenly motorcycles became socially acceptable to the American middle class, bless its numbers and its buying power.

Now, with its three new Hawks at the ready, Honda is set to attack the next level of resistance—the widespread notion that motorcycles are hard to set in motion, hard to keep upright once in motion, hard to stop and generally about as easy to manage as a brace of cheetahs in a meat market.

Capturing recalcitrants who believe the foregoing is no easy matter, and it’s hard to see the Hawks as the great emancipators of imprisoned two-wheeled souls. Not all three of the Hawks, at any rate.

But the new bikes do offer a couple of fresh and thoughtful touches—a smooth update on the familiar four-stroke vertical Twin and a condensed version of Honda’s automatic transmission to go with it. We aren’t quite as excited about these offerings as Honda is. but there’s no denying that they are more than noteworthy.

Since the engine and automatic transmission are the subjects of a technical takeout accompanving our test story, we confine ourselves here to operating impressions collected by the staff. The new threevalve 400-cc Twin delivers more punch than anyone expected, and isn't at all reluctant to run at high revs. It begins to come on around 7000 rpm, which is still 2500 rpm short of peak horsepower. Redline is 10,000. Peak torque comes in at 8000. (Both these figures are lower on the automatic edition.)

However, powerband characteristics aren't really germane to Honda’s effort to expand the market. More important are the questions of vibration and general response. Honda has tackled the former problem by installing a system of counterrotating balance shafts inside the engine. an engineering technique introduced to the American motoring public a couple years back by Mitsubishi in the Dodge Colt. It's a system that works, and works well. There's still vibration, of course, but now the mirrors don't begin to blur until the speedometer hits 50 mph or so. With out an oscilloscopically-backed compari son. our hipshot feeling (literally) is that this Twin is clearly the smoothest in its class. Moreover, in achieving this smooth ness, Honda's R&D guys managed to eliminate most of the cold-bloodedness that seems inherent in so many other Hon das we've experienced. The new Hawks start right now, and response willingly to all throttle commands.

Enough is made of the automatic transmission elsewhere in this coverage for us to confine ourselves'here to this observation: In Honda’s wooing of the Recalcitrants, the automatic looks like the probable key to success, and it works very well indeed. For riders who’d rather shift for themselves, the Stage I and Stage II Hawks offer a very slick 5-speed gearbox. There’s not an ounce of hesitation or stick in it anywhere, going up or down, and the ratios are well chosen for good low and mid-range acceleration, as well as riding two up.

which the Hawks accomplish without much enthusiasm but with plenty of determination. The Hawks begin sounding pretty busy above 70 mph, but Stages I and II will get up to the 100 mph neighborhood if you’ve got some room to take a run at it.

All this buzzing around at fairly high revs hasn’t produced a really salutory effect on fuel economy. None of the Hawks managed 50 mpg, a figure that should be within easy reach of a 400-cc machine. Predictably, the automatic was lowest at 44.6 mpg.

Honda has surrounded its new machinery with an impressive new 54.7-in. wheelbase bike, a compact package that manages to look and feel as rangy as some larger machines. The ride is good, but not the strongest point of the bike. It’s a trifle on the stiff side, and during the course of our testing we encountered a pronounced high speed wobble when we pressed the bikes hard. The source of this seems to be the top clamps, which fasten to the stanchion tubes with the top nut, similar to the British practice. This allows a certain amount of flex in the steering assembly under hard going, and could account for the wobble. It’s a cost-cutting installation and we’d prefer to see something stronger.

None of this prevents the new Hawks from being sweet handlers. They’re nimble and sure-footed, tall enough to convey something of the athletic feeling of a classic British Twin and stable enough to be ridden quite aggressively. Part of this> sporting character is attributable to a consciousness of mass centerization in development of the bike—Honda’s design engineers have been thinking center of gravity in positioning the bike’s various components—and part of it to the new Bridgestone tires, developed specifically for the Hawks. Fronts are 3.60Sxl9, rears 4.10Sxl8. They offer the same outside diameters as the 3.00x19/3.50x18 combinations commonly offered on competing bikes, but afford a somewhat wider footprint and seem well suited to a wide range of uses. In particular, they show a commendable appetite for fast cornering.

CB 400A

CB 400T1

CB 400T2

Honda CB400A

Honda CB400T1

Honda CB400T II

Forks are conventional Showa, but lack the impregnated top bearing charac teristic of late units. Ride is marginally stiff, but compliance over road irreg ularities is adequate. After less than 800 miles, however, the unit tested exhibited scoring on the bottom of the slider. As the forks wear, slider/tube friction will increase, resulting in a stifler ride. Tests performed at Number One Products

REAR SHOCKS

Shocks on the Hawk are forward mounted, hence spring and shock rates are higher than those found on com parable bikes. Honda has incorporated relief valves which reduce damping at high velocities, for a softer ride over harsh bumps without sacrificing con trol. Oil capacity is minimal, but shocks show little fade even when hot. The use of clevis-type top mount makes installa tion of existing aftermarket shocks im possible without modification.

The relationship between pilot and controls was judged good to excellent by staff riders. The handlebars, which seem to be slightly smaller versions of the GL1000 bars, drew the least praise. Their angle tends to force some riders into a more upright position than they care for, but no one experienced any actual discomfort. In fact, general rider comfort seems to be a strong point with the Hawks.

Styling is always a matter of personal tastes, of course, and you will obviously make your own judgments about the looks of these machines. Staff reaction to the bikes seemed to favor the Stage I treatment. Overall the feeling seemed to be that the bikes were gracefully done up but might benefit from a little less striping. The tank line of the Stage II and Automatic editions didn’t find much support. Both these bikes are available in black, incidentally.

Aside from the wobble, which is only experienced at the bikes’ upper limits, our biggest complaint with the conventionally driven Hawks concerns the old slop-inthe-driveline flaw. The clutches are cooperative, the gearboxes willing, but there’s still that jerkiness when one is attempting to apply or diminish power with any degree of subtlety. It’s irritating and disappointing in a bike that’s supposed to be the advance guard of Honda’s New Wave.

There are a couple other tacky touches that inspire these same emotions, both of them obviously dreamed up by some costcutter who’s going to make a name for himself (that name will differ depending on who’s supplying it, the consumer or Honda’s in-house bean counters). One complaint is the gas cap cover, which is hard to operate as well as cheap-looking. The other is the fork lock. Instead of its excellent combination ignition/fork lock, Honda has reverted to a cruder model that mounts below the triple clamps. It’s probably much cheaper, and certainly looks it.

The Hawk kickstand is a particularly treacherous piece of equipment. It’s hard to locate, particularly at night, because only the tiniest tab sticks out from under the muffler. It also likes to pretend it’s working when it’s not—be sure you pull back firmly on the bike before leaving it to the mercy of the side stand.

Seating on the Hawks is comfortable, but the Stage II and Automatic models come equipped with a moderate two-plane setup which we are on record as opposing categorically—all of them. The Stage I has a more level seat, but even this one resists anyone sitting atop or behind the alleged passenger safety strap.

Up top we find the headlamp still wired into the ignition switch and we still would rather turn the headlamp on for ourselves. Also, the handgrips seem a bit firm; if we owned a Hawk, we’d probably change them straightaway. There’s nothing new about this situation, however.

At the other end of the bike, we’d like to hear something a little more melodious in the way of an exhaust note. There’s an exhaust note in there somewhere but it’s been thoroughly muzzled between the socalled power chamber and the muffler baffles. All that emerges is about 80 db worth of putt-putting that sounds severely constricted, to say the least.

All of the foregoing is generally common to all three bikes. However, each of the Hawks also has characteristics of its own. to wit:

HONDA HAWK 400A

Given Honda’s goal of converting the hitherto unenlightened to the ways of two wheels, what we have here is the most plausible tool yet cobbled up for winching would-be bikers out of the closet. Hawks Type I and II may be solid variations on the 400-cc theme, but this piece is The Answer—a true motorcycle that requires only the most minimal participation from its rider.

Never mind that it’s a good deal slower than its brothers through a quarter mile, and that it lacks their spirited, wheelstanding character. You learn to appreciate the genius of this machine when you watch an absolute beginner climb aboard and

start circulating smoothly around the parking lot with only the slightest hint of the first time totters. Freed of the intimidating coordination requirements of clutch and ordinary gear box, the beginning rider can make the transition from four wheels to two with an absolute minimum of fuss, emerging at license time with a machine

that will handle any kind of traffic situation. None of this moped stuff.

Perhaps the richest harvest of new riders awaiting this machine is in the female ranks. We don’t mean to suggest this is necessarily a girl’s bike—virtually all of the ladies who tried it complained of its weight, to our surprise—but its ease of operation did entice ladies of our acquaintance who had steadfastly refused trying any other two-wheeled device offered them. However, beginning male riders won’t have to worry too much about second class citizenship when they show up on a new 400A—provided they avoid stoplight warfare against conventional machinery. Honda has gone to considerable trouble to make the Hondamatic Hawk look exactly like the Stage II version, up to and including a bogus clutch lever that actually operates a parking brake.

Aside from the side decal, and the gear indicator lights in the right-hand instrument pod, there’s no other immediately visible difference between the 400A and the Stage II. It’s like having a wooden leg. No one will really be sure until you start to sprint.

Slow is a relative concept, of course. If you want to talk about middleweight rockets, the Honda 400A won’t even creep into the conversation. The Hondamatic is slower out of the blocks than bikes with half its engine displacement, but once rolling, say from 30 mph or so, it motors along creditably enough, with sufficient power reserves to zip through traffic. Calling this quality quickness would be stretching a point, so let’s put it this way: The 400A will never make you late for work.

continued on page 90

continued from page 65

The main thing holding the Hondamatic back in stoplight drag racing is the Hondamatic. It was slow in the 750 version introduced last year, and it is even slower in the miniaturized edition hitched up to the new 400 Twin. However, the premium for automatic transmissions has always been paid in performance penalties, and the Hondamatic offers substantial credits to balance these debits. It does its job smoothly and with remarkable efficiency, whether the bike is run up in second gear or operated as a clutchless 2-speed. (You must relax your death grip on the throttle to shift, incidentally. Although Honda claims you can upshift under full power, we found that power shifts produced a lot of complaints from the auto’s innards.)

Using both speeds is preferable for most street applications. Moreover, it eliminates the drive line grabbiness that continues to plague chain drive motorcycles.

An especially nice touch, considering the primary intended market, is the kickstand/drive interlock. When the stand is down, you can light the engine, but it shuts off automatically if you attempt to put the bike in gear before folding the stand.

There are a couple of side effects to the automatic that take some getting used to. As you might expect, the 400A exhibits a slight tendency to creep forward at stop lights, which could be embarrassing if you’re daydreaming. Perhaps more disconcerting during the getting acquainted stage is the absence of compression braking. When you turn down the wick, the 400A simply starts coasting—the little torque converter may be ingenious, but it’s pretty much a one-way item. However, since the brakes—front disc/rear drum—are up to Honda’s usual high standards, the absence of engine braking isn’t really a problem, particularly for newcomers, who won’t miss it in any case.

continued on page 92

continued from page 90

The torque converter isn’t the only thing that keeps the 400A’s performance well short of neck-snapping. In order to accommodate the engine to the automatic, it was detuned somewhat, roughly 10 hp worth. This was accomplished by employing smaller venturis in the twin Keihin carburetors—28 mm in the 400A and 32 mm in the others—and smaller intake and exhaust valves. The 400A uses 21-mm intake valves and 26-mm exhaust, compared to 26-mm intakes and 32-mm exhaust in the other bikes. Couple this with a slightly heavier engine package (11 lb.) and heavier bike overall (14 lb.) and you have another big reason why this machine will rarely be seen going away when the light turns green.

To which the ladies of our auxiliary test corps reply, “So what? That stuff doesn’t matter to us.” We harp on this perspective because it’s so easy to lose track of.

What does matter is that this machine does what it’s supposed to do, and does it well. Although there are detractors who equate learning to ride on an automatic bike with learning to drive in an automatic car—it’s like sitting down to play chess without knowing the knight moves, or what en passant is all about, they say. But from Honda’s point of view, the idea isn’t to create Bobby Fishers overnight; the idea is to get these people to the board. The subtleties can come later.

We think the Honda 400A will succeed where the 750A didn't. The original Honda automatic has caught on with some tourers, but its sheer bulk kept it from getting many new riders into the sport. We think the Hondamatic Hawk, a solidly conceived and beautifully engineered piece of equipment, is what Honda should have offered in the first place.

HAWK STAGE I

There’s hardly anything new about the concept of a Plain Jane. It's one of the oldest traffic-making devices in the motor vehicle biz, two-wheeled or four.

continued on page 94

continued from page 93

The idea works like this: You lure all these droves of potential buyers into your showroom with the promise of a bare bones special so cheap they can’t possibly pass it up, then convince them there's no way they can possibly live with this monkish device, then sell them the high bucks deluxe model.

In the realm of cars, the difference in price between Plain Jane and loaded versions can run up into the thousands of dollars. For bikes it’s frequently a matter of only $100 to $200. But the basic idea remains the same: The company doesn’t want to sell you the economy model. They merely wish to entice you with it.

We feel Honda is violating this basic tenet with the Stage I Hawk. It definitely fits the no frills parameters, all right, but we have a very strong hunch that Honda actually wants to sell this bargain bike. We have two clues: First, the Stage I looks substantially different from the Stage II. It has wire wheels, a tank that looks like something from England circa 1968 (Honda calls it a “strong, brawny tank design”), and a seat that pretty much avoids the twoplane setup offered on the Stage II. Second, Honda is pricing the Stage I some $200 under the Stage II. (As we went to press, the Honda marketing people were talking about approximately $1 100 for Stage I, $1300 for Stage II and $1400 for the 400A, with none of the above final as yet.)

Here’s what that $200 represents in terms of missing equipment. Besides its wire wheels (the other Hawks have Honda’s ComStar wheels), the Stage I has drum brakes at both ends, no electric starting, no tach (the right-hand instrument pod carries warning lights for high beam, oil and neutral as well as the turn signal repeaters), and no center stand.

Despite these deletions—or perhaps because of them—review’ of the Stage I around the CYCLE WORLD water cooler was generally favorable. The styling seemed more acceptable than that of the Stage II to most staff members, if for no other reason than familiarity, and we’ve encountered few two-plane seats that we’ve liked. The kick starting wasn’t a particularly big handicap because Honda’s new 400 Twins start and run willingly and because we don’t live in a hilly place like San Francisco. The wire wheels seemed to be an asset for some potential buyers, usually those who like wire wheels and don’t like the looks of the ComStar. And because it’s about 20 lb. lighter than the Stage II. the Stage I Hawk is the quickest of the trio.

At the Hawk’s introduction, in fact, some Honda people were calling the Stage I Hawk the performance model, which is stretching the point a bit since performance involves stop as well as go and braking is not a strong point with this machine. Stopping distances from 60 mph were only average, and the bike exhibited a good deal of front wheel hop.

Aside from its stopability, however, there isn’t too much fault to find with Honda’s new bargain Hawk. It gets around with a little more zeal than its more expensive brothers, and offers a look that is certain to be appealing to traditionalists, at the very least.

This is the bike that will probably put an end to Honda’s previous bargain bike, the CJ360. It is also a very strong contender for best buy in its class.

HAWK II

The Stage II version of the new Honda Hawk is a very sophisticated 400-cc Twin, embodying almost everything that’s new and good in the 400-cc Twin biz. This is a fortunate thing for Honda marketing, because the Stage II Hawk is in the ring with some very tough competition—the Yamaha XS400D. the Kawasaki KZ400 and the Suzuki GS400, solid, attractive bikes every one of them.

However, the new Hawk stacks up well. It’s quicker than all but the Yamaha, which shades the Hawk II by a matter of a few hundredths of a second in the quarter. It's within a few feet of the best stoppers in that group—the Hawk, Yamaha and Suzuki all haul down from 60 mph in less than 120 ft.

Beyond these considerations, it gets to be largely a matter of handling and styling preferences. As mentioned earlier, we feel the Hawk shines in the former category, and may just be best in its class. And as far as styling is concerned, we feel the Hawk Stage II at least holds its own. We don’t care much for the looks of the tank, but the rest of the package has a graceful, lean look that squares quite well with the bike’s surprisingly sporting character.

There’s one piece of bad news concerning this new Honda, or perhaps potential bad news is a more accurate description. The arrival of three new bikes puts considerable pressure on the marketing troops to weed out the already overgrown model line, and the logical place to start weeding is in the immediate vicinity of the newcomers.

Honda is playing this very close to the vest, so as to avoid choked outcries from its dealer network, but it doesn't take much vision to see the 360s disappearing in the not-too-distant future. No cause for sorrow there. But it seems likely the excellent little CB400F, which is reportedly a good deal more expensive to produce than the new Twins, will take the deep six as well.

The 400 Four has been sustained in the lineup to date only as a result of dealer pressure, according to insiders, and even though the Hawk is a totally different motorcycle it seems likely the town ain’t gonna be big enough for both.

Too bad. 5!